Brett Feldman, PA-C

Los Angeles, California

Brett practices street medicine with Los Angeles’ homeless population

“In LA we’re fortunate to have many options for getting people off of the street that we didn’t have when the pandemic. This includes motels for those who are high risk but asymptomatic, as well as isolation and quarantine sites and a separate site for those diagnosed with COVID-19. The trouble in LA, as it always is, is the amount of unsheltered homeless makes it impossible to place everybody. It’s estimated that even if all the beds made available were filled, there would still be over 30,000 on the street on any given night.

If we can’t move them into shelter or it isn’t in their best interest to do so, we do our best to shelter them in place. Physical distancing in camps involves separating tents at least 12 feet apart, providing tents to each person for a tent to each person goal, and creating handwashing stations out of household materials such as water jugs. There is a thought that those who live in small encampments, or already in isolation, may be better off staying where they are rather than moving into a congregate shelter. For these people, we try to make it as safe as possible for them and the community.

We are handing out hand sanitizer but not masks. Masks need to be cleaned to stay sanitary. Most people living on the streets don’t have access to supplies needed to do this. If the masks become unsanitary, it puts them at higher risk than not wearing them at all.

There are existing challenges made more difficult during the pandemic. Soup kitchens and other groups who usually provide food are either not doing so, or are but on a limited basis. Public buildings where they would normally go for some respite during the day are closed down.

The new challenge we are seeing is hospitals around the county are trying to keep their census down for COVID -19 patients. As a result, people who would ordinarily be admitted are being discharged home.

The ED is still the primary location those we serve go for care. When this happens, people rely on community clinics to care for sick patients who would’ve been hospitalized. Instead, community clinics have switched to telemedicine. This may be okay for the housed population, but those we serve don’t have access to telemedicine services, and if they do have a phone, they likely don’t have a place to charge it anymore. The result is further isolation and even further decrease in access to care. Finally, if they do get sicker, they don’t have the ability to call for help or 911 with a dead cell phone. This makes street medicine and other outreach services even more vital during this time.The challenge is that in most cities these services either aren’t in existence or so under resourced that it won’t be enough. Hopefully we will learn from this in the postmortem analysis of the COVID-19 response.”

Rebecca Bruce, PA-C

Chicago, Illinois

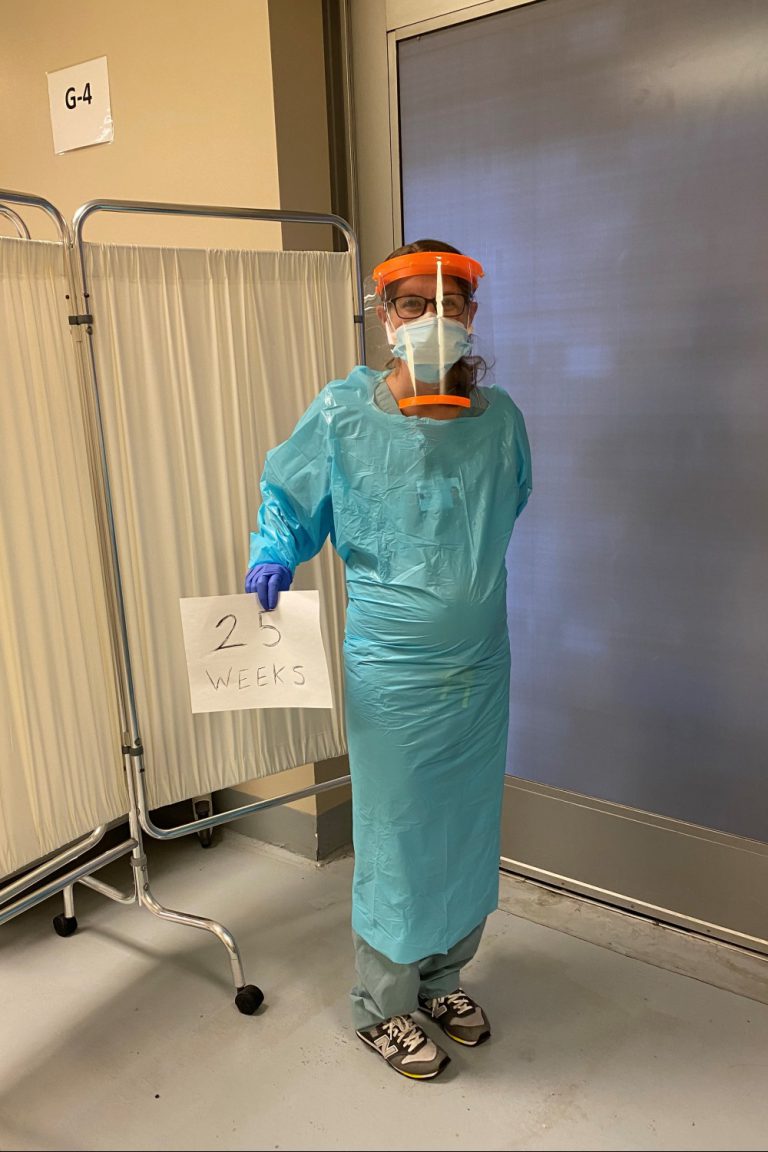

Rebecca works at a hospital emergency room in a diverse suburb of Chicago. She is also 27 weeks pregnant.

I work in the ER so all of our patients we suspect could be positive for COVID-19 from being out in the community. We always prepare with a gown, gloves, N95 mask and a face shield. We have what our ER calls a “COVID Corner.” It’s like a COVID tent where we generally see the walking well (patients with normal vital signs and no comorbidities). We swab them, and have the ability to do labs or a chest x-ray if needed. Most of the patients are able to go home and self quarantine for 14 days with good return precautions. Our hospital is fortunate enough to have a team who then calls the patients a couple of days after their visit to check in on the them and make sure they are doing well if not they are told to come back to the ER immediately.

We have not had a huge influx of patients in our ER, and due to the low numbers our group has decreased physician coverage and increased advanced practice provider hours. I have actually worked a lot more hours this month than I usually do. I’m working approximately 160 hours this month, when I usually do 120 to 125 hours.

We are seeing a range of patients in our Emergency Room. Most patients are very concerned and want to be tested because they are working in factories, grocery stores, or are health care workers on the front lines. They are working with co-workers who have tested positive, and they are concerned about infecting their families. We are also seeing very ill patients from nursing homes who have a multitude of medical problems which set them up for a poor outcome when also being diagnosed with COVID-19.

As a physician assistant our job is to educate. We are doing a lot of education with our patients, reminding them to go home, self quarantine, not go to work and not go out into their communities. We are educating patients on wearing a mask if unable to socially distance themselves from others. We also see patients who live in households with multigenerational families, where they can potentially get their grandmother or cousin sick. It is important that patients are well informed about the virus especially if English is not their primary language. I often have to use an interpreter which is one extra step, but is extremely important when educating my patients. I strongly believe that the community can be misled and misinformed by the media, and proper education is an important step as a health care provider on the front line.

I’m being very cautious [since I am pregnant]. My stress level has increased. I recently failed my one-hour glucose test even though my BMI is on the lower end and I have an overall healthy diet. I had no idea I would have diabetes, but I think the stress level is probably increasing my cortisol, which is increasing my sugars unfortunately. I have my three-hour test tomorrow, but I’m already doomed that I might fail, so I think that’s kind of affecting the pregnancy. It’s hard to be a pregnant woman and still go to work to begin with. I’m being extra cautious by wearing proper PPE, but at the same time I’m concerned that I could bring something home to my husband or pass it on to my child and that’s scary.”

Aakash Shah, PA-C

New York, New York

Aakash specializes in orthopedic surgery and occasionally in internal medicine, but has now turned his focus to fighting COVID-19.

“I work full-time in orthopedic surgery, in-patient in the hospital. I also do some outpatient internal medicine once or twice a week. Right now, I’m not doing either of those and I’m doing COVID-19 cases. New York City is one of the hardest hit cities in the country, if not the world. Basically, the entire hospital has evolved into just one department, and that’s a COVID-19 department. Everyone in the hospital is just doing COVID-19 cases left and right.

A normal day before COVID-19 was getting on a packed subway train during rush hour. I’d make my way to the hospital and fix fractures and dislocations and all things orthopedic. Now I’m going on this empty train where I see like maybe three or four [other people] in scrubs around me. It’s all essential workers. We’re all going to the hospital.

I manage COVID patients on the floor. I will have about 25 to 30 COVID-19 patients on the floor. A lot of these patients are not healthy patients, and are admitted into the hospital because they have underlying comorbidities.These patients are very sick, and they decompensate very quickly.

I had a 54-year-old, fairly healthy guy with a history of high blood pressure. He was doing well throughout the day. Around 9 pm, he started decompensating where his oxygen saturation went from 92 percent to about 88 percent on nasal cannula. We escalated him and put him on a non-rebreather mask. Despite being on the non-rebreather, he continued to decompensate. We had to escalate it more and incubate him. On my shift the next day he passed away.

As a provider, not only do you have to take care of the patient, after the patient dies, you have to inform the family members. That’s where the emotional toll comes on. For this 54-year-old man, he had two daughters. One was a teenager and the other in her mid-20s. So, breaking that news, it’s kind of tough. You’re running around the hospital, you’re physically exhausting yourself, you’re dealing with family members and death on a daily basis now. I think some health providers are getting hit from all sides.”

.